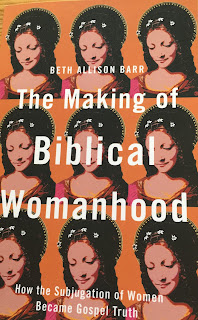

The Making of Biblical Womanhood: How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth

A deconstruction of complementarianism showing how it is not a recovery of a historical or scriptural understanding of the role of women in the church and family.

Barr tells something of her own story of growing up and ministering, with her husband, in complementarian churches, and of suffering abuse as a result of this teaching, as well as her change of mind and walking away.

Barr’s approach as a historian is interesting as she focuses on historical material, especially her specialism of medieval history, to show that for much of church history women have preached, and have been accepted as so doing. She identifies the Reformation as a downturn for the recognition of the calling of women to ministry, as well as the mid-20th century with world wars and the rise of the Council for Biblical Manhood and Womanhood.

This latter Barr links to the rise and hardening of the inerrancy movement in relation to scripture and also to the Arian heresy of the subordination of the Son to the Father within the Trinity.

Barr also discusses how English Bible translations have played a fundamental role in shaping understanding in this area, and how the ESV was prepared specifically to defend the subordination of women by responding to the move for gender inclusive Bible translations.

In an interesting discussion (pp.148-150) Barr refers to the Hebrew word which can be translated as either woman or wife. In Genesis 2 choices are made as to how to translate the repeated use of this word to create a certain picture, and so “The English Bible translated more than Hebrew text; it also translated early modern English ideas about marriage into biblical text.” As the word marriage appears nowhere in the OT Barr points out that some women are called wives who never would have been in the biblical world. I would like to have seen more on this.

Barr discusses the usual ‘problem passages’ from the Pauline letters, observing that they would have had a liberating effect for women in the original Roman context, and that they were not read as restricting women for much of church history. Barr follows Lucy Peppiatt (and others) in seeing some of Paul’s writing as being dialogical, i.e. quoting his opponents position as well as stating his own.

Barr acknowledges that the church has been patriarchal for much of its history, but describes how the form patriarchy has taken has changed through history, and that the church has been mirroring society in this way, not mirroring scripture. It is only in recent times that patriarchy has become ‘sanctified’ by its linking to particular interpretations of scripture (which are modern, not historical, interpretations).

Actually Christians are called to be distinct from the world, declaring the Kingdom values of freedom – in Christ there is no male or female.